There was a time when Malcolm Fraser was my poster boy for arch-conservative bombast. When I was student in the early 80s, his then infamous “razor-gang” was busy cutting the heart out of the wide-ranging education reforms of the Whitlam era, the same reforms that had enabled me to be the first of my family to attend university.

Like many at the time, I took that personally and seethed with the indignation of the young. I wrote placards and marched but ultimately achieved very little except getting in the way of his prime ministerial car as he flashed past on his way to meeting.

For me, Malcom Fraser represented all that residual passion that I felt in the aftermath of the Whitlam dismissal, the event that many believed was destined to define Fraser and his legacy as prime minister.

That view has softened considerably over the intervening years. Years after graduating, and years after becoming a journalist, I had an opportunity to interview this eloquent giant in his Melbourne office in 2004.

By then, Malcolm, who should have been regarded as an elder statesman of Australia’s conservatives, was instead regarded as a Liberal Party maverick and a thorn in the side for John Howard’s government which was then flexing its considerable political muscle, and gaining electoral traction, over the highly volatile issue of asylum seekers and so-called “boat people”.

He viewed the Howard Government’s demonization of these asylum seekers as something that did not belong in his concept of liberalism.

He was, he said, a liberal in the sense that Robert Menzies – Fraser’s mentor – was when he headed the Liberal Party during the ’50s, someone who believed in liberalism’s rationality, resilience, beauty and pragmatism and who believed that government should be dedicated to the pursuit of human advancement, prosperity and happiness.

His government had similar problems, he said, with refugees after the Vietnam War. They had considered solutions such as turning back the boats, detention centres and offshore processing.

But the Fraser Government rejected all those options, he said, instead opting to accept more than 250,000 Vietnamese refugees and immigrants because that was the right thing to do.

He told me a story about how he went to the pub – something Fraser liked to do, even as Prime Minister – in his local electorate of Wannon back in the late 70s when the refugee crisis was at its peak. He recalled a local farmer telling him he didn’t want “them” here in Australia.

He went back to the same pub a year later when the same bloke complained that his son had become engaged to “one of them” – meaning a Vietnamese girl. A few months later, the farmer had changed his tune. That girl – one of “them” as he had eloquently put it – had become “the best thing to have ever happened to his family.”

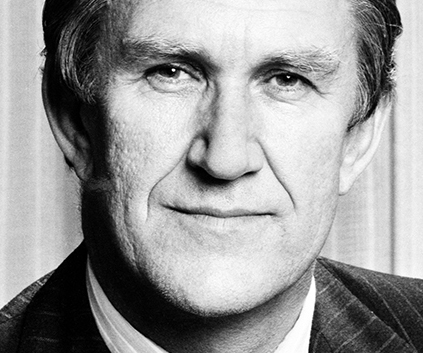

He told this story with apparent relish, leaning back in his leather-bound chair dressed in the same immaculate style of pinstriped suit that I remembered him wearing as Prime Minister. And he told with that same plummy, eloquent voice that I had once ridiculed for its arrogance and born-to-rule attitude.

However, I did not hear any arrogance or even a hint of “born-to-rule” that day. Something had changed. Whether it was he or I, I couldn’t really be sure. But if I was a betting man, I’d say the most significant change was probably with me.

I got the sense that Malcolm’s conviction came from deep within, something innate, not from some self-serving revisionism.

I walked out of his office several hours later after discussing many parts of his life – including the events of the dismissal which he maintained was absolutely necessary in the circumstances and even that time he lost his trousers – with a changed view of him, in much the same way I think that many Australians changed their views about him.

I came away with a newfound respect, not just for his views but for his courage in expressing them at a time when it might have been easier just to fade into the distance.