In every suburb, every day, people are producing, viewing and sharing unfathomable quantities of child sex abuse images on the “dark” web. The story of who they are is deeply disturbing, but more alarming is our failure to protect the victims – innocent children. Clair Weaver reports on a topic no parent can afford not to read.

WARNING: This story contains disturbing details

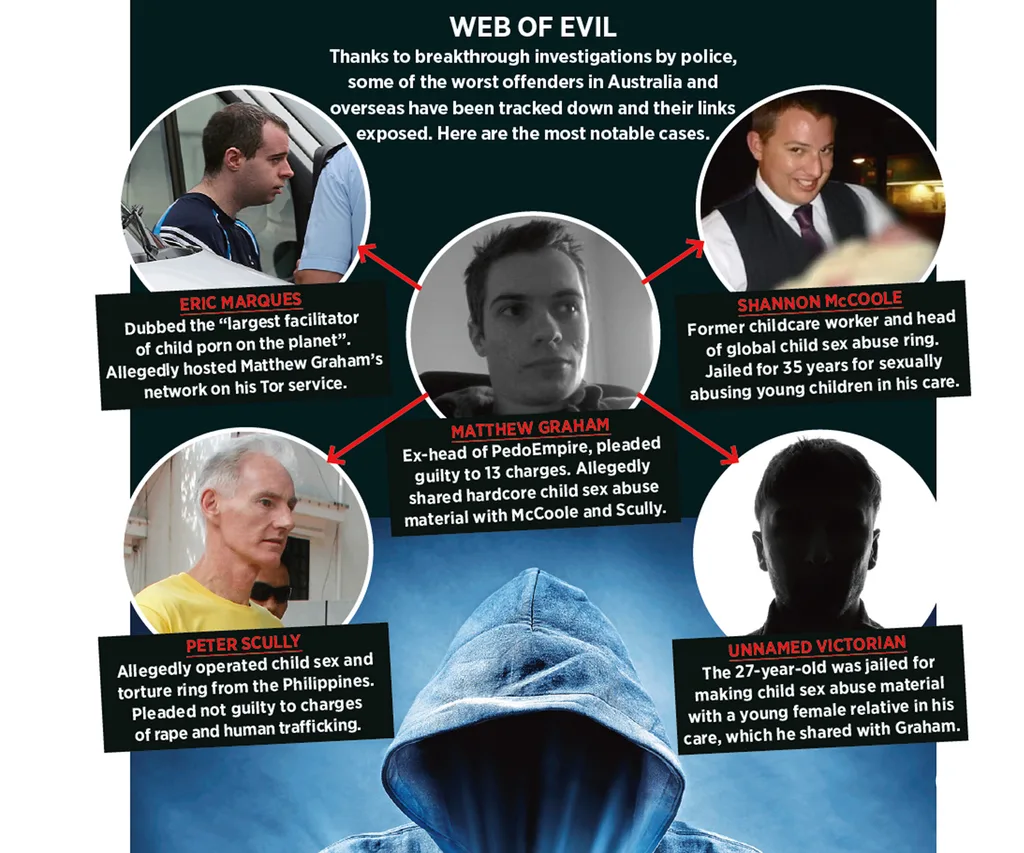

If you’d met an awkward 22-year-old called Matthew David Graham a couple of years ago, you wouldn’t have picked him as the kingpin of a global web network.

The skinny nanotechnology student, whose cheeks were ¬ flecked with acne, spent most of his time hunched over the computer in his bedroom at his parents’ home in a nondescript suburb of Melbourne.

On the surface, he was simply an avid gamer who felt more at ease in the virtual world. In real life, he kept to himself and sometimes babysat for children in his neighbourhood.

Unbeknown to anyone, however, Graham had a secret identity online.

In the dark web – an anonymous place out of reach of Google, where purveyors of drugs, weapons and child sex abuse material lurk – he was an in¬fluential tech guru called “Lux”, who ran an underground network called PedoEmpire.

Drawing on his computer skills and emergent paedophilic urges, he built, from the age of 18, the worst empire of child exploitation sites ever seen.

So profoundly disturbing and explicit was the nature of the material he collated and disseminated to members that most in the online paedophile community shunned it.

It’s a genre known as “HurtCore”, which includes violence, torture and acts of extreme depravity against children and babies.

¬

Meanwhile, in another unremarkable suburb 760 kilometres north-west of Graham’s darkened bedroom, a young man whom you probably wouldn’t have picked as a child sex offender either was also sitting at his computer. Shannon McCoole, a baby-faced social worker for Families South Australia, was busily uploading images and videos of himself sexually abusing young children and babies in his care. None showed his face.

Using the pseudonym “Skee”, he controlled an international child sex abuse bulletin board on the deep web, which cannot be named for legal reasons.

The 45,000members of his network – the world’s biggest child abuse site – were obliged as a condition of membership to share a continuous stream of child sex material. Highranking contributors could win VIP status; those who failed to do so would be expelled.

McCoole, an Adelaide man who had no criminal history or red flags over his employment history, was responsible for caring for children at a government residential facility and an out-of-hours school care service.

This meant McCoole had unfettered access to the most vulnerable and voiceless of kids with a very low risk of being caught. His seven victims were preschoolers in state care and included a child who was disabled, another who had autism and an 18-month-old baby.

His own supply of material to his creepily named site was prolific. At Christmas, he would send fellow administrators videos of himself raping children as a “present”.

McCoole’s network had an exclusive “producers’ area” for top contributors or those who produced abuse on demand – and members included Lux, aka Matthew Graham.

More than 5000 kilometres north of McCoole’s cluttered home, yet another Australian was also allegedly running a child sex abuse ring, this time from the impoverished nation of the Philippines.

Peter Gerard Scully, now 52, is believed to have offered live pay-per-view video streaming of Scully, who is from Melbourne, is accused of sexually abusing and trafficking young girls and babies from desperately poor families. He is being investigated for the murder of a 12-year-old girl, whose skeletal remains were found under a house that he had rented. Further serious charges are expected to be laid against him by Philippine Police.

Closely linked to Scully was Matthew Graham, with the pair allegedly sharing hardcore material online.

All three men were using the dark web or darknet – the encrypted criminal corner of the deep web – to anonymously communicate as well as share, swap, trade and download child abuse material. You might assume this is the niche domain of a warped minority, but you’d be wrong. While the likes of Graham, McCoole and Scully may have been high-ranking distributors, plenty of everyday Australians are looking at this kind of material. For the confronting and unpalatable truth about child sex abuse online is that it’s everywhere – and it’s likely being accessed somewhere near where you are right now.

“In every major city and every country town, there will be someone who is sharing these images,” Detective Inspector Stephen Dennis, who runs Victoria Police’s joint anti-child exploitation team, tells The Weekly. “It’s right across the state, the country and the world … that’s the reality.”

The Weekly understands that police have witnessed homes lighting up at a suburb level on computerised maps during investigations, as users share and download new material (the term “child pornography” is no longer used of¬ficially, consent, but is still in the vernacular of dark web users, along with the acronym “CP” and slang such as “cheese pizza”, “hard candy” and “lolitas”).

While its hidden nature makes of¬ficial statistics hard to collate, the sexual exploitation of children online is an entrenched and growing problem.

Jennifer Cullen, the co-ordinator of child protection at the Australian Federal Police (AFP), says her department has seen a 100 per cent annual increase in referrals for people accessing material over the past few years – and that’s probably the tip of the iceberg, given most cases go unreported.

“It’s prolific and it’s growing by virtue of expansion of access to the internet,” she says.

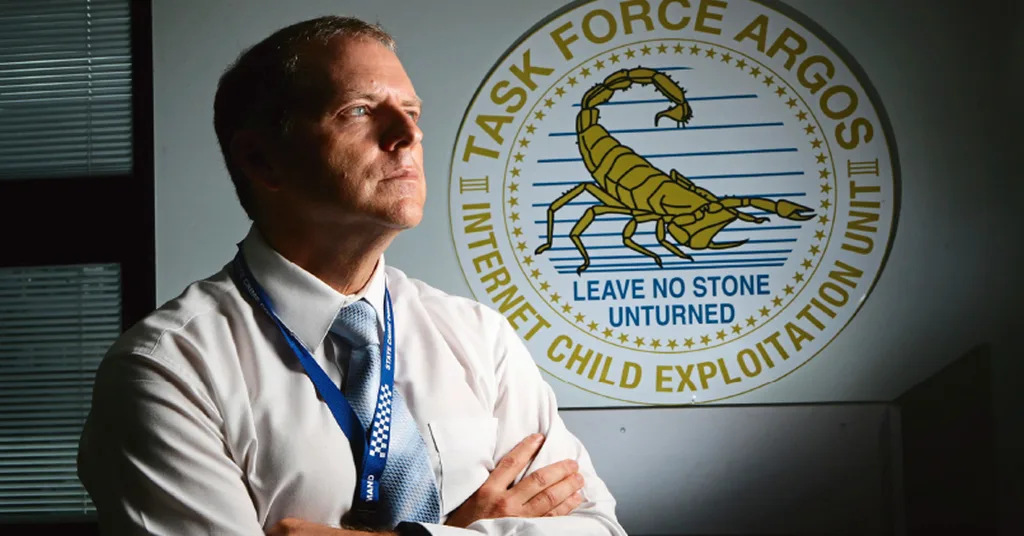

Likewise, Detective Inspector Jon Rouse, of Queensland Police’s Task Force Argos , which brought down McCoole in a groundbreaking two-year operation, has seen a tenfold increase in arrests and victim identi¬fications since the 1990s.

Five years ago, the United Nations estimated 750,000 people were looking at child sex abuse online at any one time (that ¬ gure would be higher today). One in 1000 accesses it at work, according to technology provider NetClean, reducing their risk of being found out on a family computer.

For users, there’s no shortage of material in cyberspace, as police ¬find when they swoop in for a raid. “It wouldn’t be uncommon to have a seizure of in excess of one million images,” says Inspector Dennis.

¬No matter how appalled you are by all this, you probably know someone who has looked at child sex abuse online. Maybe it stemmed from viewing adult porn, curiosity, chat forums or latent attraction. So are they all paedophiles? Or is the easy availability and accessibility online desensitising viewers, feeding demand for more extreme material or creating a new appetite where it may not have existed before?

“The general community tends to think anyone who engages in child sex abuse is a paedophile,” says Dr Katie Seidler, a clinical and forensic psychologist. “But if you take 100 convicted child sex offenders, about 5 to 10 per cent would actually be paedophiles [a person whose primary sexual attraction is to children, as opposed to someone who is mainly attracted to adults, but abuses kids].”

The remainder, she says, would include people with social deficits who fear or cannot handle adult relationships and those looking for easy targets. For them, children are more suggestible, less judgemental and easier to control than adults.

Most disturbingly, Dr Seidler describes how simply viewing child sex abuse as erotica may create new pathways in the brain of a person who has no history of an attraction to children, creating a destructive new feedback loop.

“Some people are heavy users of online porn and can become sanitised to what they are seeing,” she says. “Ten per cent of their [viewing] might be child sex abuse … but if you watch that material and reinforce it with masturbation, you will condition yourself to be aroused to children. So you can become conditioned.”

Indeed, few viewers start out specifically seeking child sex abuse online, according to Swedish psychologist Hanna Harnesk.

“[They] start by consuming adult pornography, which by degrees goes over to include material depicting child sex abuse as well,” she says in The NetClean Report 2015. “It is not rare for there to be a strong compulsive link to the consumption of child sex abuse material.

These individuals view the child as an object and do not think of the child as a real child capable of feelings and suffering.”

Incredibly, some who become involved with the dark web’s close-knit child sex abuse community don’t even have a sexual interest in children.

This may have been the case with Eric Eoin Marques, a young Irish loner who allegedly hosted Matthew Graham’s PedoEmpire and Shannon McCoole’s network on his anonymous server Freedom Hosting before his arrest in 2013. The FBI, which is still trying to extradite him to the US, has described him as having been “the largest facilitator of child pornography on the planet”. Eric’s father, however, has insisted he provided profitable infrastructure, but wasn’t involved in the content of the networks he hosted.

Similarly, Matthew Graham has claimed he wasn’t into “HurtCore”, but believed in the right of others to have a place where they could view it. This may, of course, be untrue.

Dr Seidler says the men who view child sex abuse material online, but don’t act on it, are more likely to be higher functioning people, married and in a professional career. Detective Inspector Rouse says “many have children of their own and are … living this kind of lie”.

Along with other distorted justifications aimed at assuaging guilt, many people will try to justify their dark online habit as “I’m only looking”.

Perhaps this is true in some cases (Dr Seidler says most viewers won’t go on to abuse kids in real life, but should seek help; Detective Inspector Rouse says anyone who gets sexual gratification from looking at images of children is a potential threat), but, either way, it’s really no excuse. Viewing creates demand, which is met with supply, which means more kids are abused, traumatised and left suffering long-term harm. In recent years, material has become more violent and increasingly involves preschoolers and infants.

“We are seeing younger children, more graphic imagery and acts of torture,” reports Inspector Dennis. “Even those who consider themselves ‘collectors’ are feeding demand for material.”

Being exposed to that kind of material can take its toll on investigators.

“If you can look past the destruction of the images, you can work to do something about it,” says Detective Inspector Rouse, whose task force’s top priority is rescuing children, with a dedicated victim identi¬fication unit.

So why do they do it?

“You can actually make a huge difference in a child’s life,” he says. “We know the sexual abuse of children causes a lifetime of suffering, including self-harm, mental illness and suicide. If you can put an end to it when they’re as young as possible, you give them a chance of a normal life.”

Detective Inspector John Rouse says online grooming of children is frighteningly common.

Who are the victims?

There’s no quick answer here – they range from children sold into slavery and prostitution in the world’s poorest countries to tech-savvy students at elite private schools in Australia. Children, explains Inspector Dennis, are vulnerable because they are inexperienced and trusting. For those who are physically abused, the predator is most likely to be someone they know, including relatives, friends and care-givers.

Yet in an era when almost everyone has their own mobile phone, social media accounts, instant messaging apps and wireless devices, any child is a potential victim – even within the four walls of their bedroom.

Self-produced “child pornography” – which can range from nude photos taken by children falling into the wrong hands, to the depiction of videoed sexual acts on coercion from a predator, to viral distribution – has become a major source of new material. The ubiquitous mobile phone is commonly used for recording, viewing and sharing material. It sounds shocking, but while researching this feature, The Weekly came across girls uploading photos and explicit videos of themselves with the encouragement of strangers on chat forums. A darknet website boasted of hosting videos of girls who had subsequently been blackmailed into providing more extreme material (police say this is a known tactic).

Online grooming is “horrendously common” as a way to secure new material, warns Detective Inspector Rouse, particularly through apps, social media and gaming. Your child’s new friend on Kik, Instagram or Minecraft , in other words, might not be who they appear to be.

“It’s a real danger,” adds Inspector Dennis. “You’ve got someone who takes an interest in them and before you know it, you have got a child putting out images of themselves naked.”

He warns against the modern trend for kids to “sext” or send intimate photos to each other, given the risk of these images entering the realm of child sex abuse.

“Once [images] are out, they can go around the world … and you don’t know how often they will be shared and duplicated,” Inspector Dennis says.

¬

Rewind to 18 months ago. Unbeknown to Graham, McCoole and Scully, the dark web’s anonymising technology would not protect them forever. They were being watched by undercover detectives. Clues were being gathered, analysed and pieced together. Officers were swapping intelligence with child protection units across the country and with overseas counterparts in the US, Europe and Asia.

Despite their apparent bravado (using his pseudonym Lux, Graham taunted the FBI and took part in a frank interview with a journalist for internet publication The Daily Dot that was published in 2014; McCoole flippantly told work colleagues “there could be a paedophile right here in this room and you wouldn’t know it” in a meeting about child safety), the net was closing in on them.

It began with McCoole. His unconventional and ungrammatical greeting “Hiya’s” and a freckle on his hand would prove critical in his identification and downfall. Once the team at Task Force Argos confirmed it had the right man, they liaised with South Australian Police on his arrest.

From there, detectives from Task Force Argos infiltrated McCoole’s network and took over his identity as administrator for 10 months to trap other child sex abuse offenders. Graham, whom The Weekly understands had just been granted approval to work with children, would be unravelled by the seizure of McCoole’s network, with collaboration from Victoria Police, the FBI and Europol. Scully, meanwhile, had been arrested by Philippine Police after collaboration with Jennifer Cullen’s team at the AFP, which has a liaison officer based in Manila. The arrests were a victory for police, who skilfully combined advanced cyber literacy with old-fashioned detective work to track them down.

The three men are each behind bars and their online networks have been shut down. McCoole is serving a 35-year prison sentence. Graham has pleaded guilty to 13 charges relating to child sex abuse material and will face the County Court of Victoria for a plea hearing on February 3. Scully remains in custody after pleading not guilty to rape and human trafficking.

Three more Australians who can’t be named were also swept up in McCoole’s drag net – not to mention dozens of others in Europe, the US and Canada (you might wonder whether Australians are over-represented in this dark trade, but police say we’re on par with other developed nations).

It would be fair to say some of the top-ranking players in the dark world of child sex exploitation were extinguished last year and many children were saved from abuse.

Don’t breathe a sigh of relief just yet. It would be a mistake to assume this will have a lasting impact on this morally repugnant black market. “Everything we take down,” Detective Inspector Rouse says, “is replaced with something else.”

While children have been sexually abused throughout history – indeed it’s only been widely criminalised in the past 50 years – the dissemination of hardcore imagery has never been so sophisticated and prolific.

Only a generation ago, people who wanted to view paedophilic material would have had to visit a back alley adult bookshop. For many, that may have been sufficient deterrent. Today, it’s a few clicks on their computer, tablet or mobile phone in the privacy of their own home.

The arrival of the National Broadband Network will mean quicker downloads. Advances in technology will bring new challenges and new apps will provide new opportunities for grooming of kids.

Details of police investigations that emerge in court cases of offenders will help dark web users adapt to better evade detection. Meanwhile, predators will find new groups of vulnerable children and abuse will probably move into darker territory.

Nevertheless, those in the field are determined to adapt, evolve and stay a step ahead.

Detective Inspector Rouse has a warning for anyone producing, sharing or looking at child sex abuse material.

“[You] can’t be complacent,” he says. “[You] should know there’s a team out there intent on shutting you down.”

WHAT IS THE DEEP WEB AND THE DARK WEB?

The deep web is the vast underbelly of the World Wide Web that is out of reach of traditional search engines such as Google or Yahoo. Most of us see only a tiny proportion of what’s online by sticking to the “clear” or “surface” web.

Much of the deep web comprises benign stuff¬ such as databases and archives.

Within it, however, lies the “dark web” or “darknet”, which describes the space used for more nefarious purposes by drug and weapons dealers, cyber criminals and publishers of child sex abuse material.

The dark web is usually accessed through Tor, software that uses anonymising technology so users can’t be identified or traced. First developed by the US Navy as a way of protecting sensitive intelligence communication, Tor is also used legitimately both on the clear and deep web by many others, including activists, journalists, academics and whistle-blowers.

EXTRA RESOURCES

To find out more about keeping your children safe from online child sex abuse, go to thinkuknow.org.au, which has programs for parents and young people.

A version of this story originally appeared in the February issue of The Australian Women’s Weekly 2016.

Video you might enjoy: Marlon Brando graciously rejects Oscar for role in Godfather.

.jpg?fit=900%2C750)