The little girl watched as the shrieking woman waslowered into the well, her feet and hands tied. They thought she was a witch.

A woman who’d been beaten so badly by her husband she’d lost her mind.

Yordy would never see her mum again.

Yordanos Haile-Michael doesn’t know how old she is, but she has given herself a birthday, Valentine’s Day. She was perhaps three when her father took off with her two brothers and left her alone in the streets of Asmara, Eritrea, in the late ’80s. From that moment, she was an outcast, like her mother, with no one to keep her safe.

“Yordanos Haile-Michael doesn’t know how old she is, but she has given herself a birthday, Valentine’s Day.” PHOTO: Hugh Stewart.

Today, Yordy sits in a Sydney restaurant, glowing with the great beauty that brought so much brutality and unwanted attention. There is grace in the animated way she speaks and elegance in her movements. Yet, as she recalls her painful past, she tells her story haltingly and there are times when it’s simply impossible to go on.

Yordy’s is the story of an abandoned child, who became a child soldier, a refugee, a mother, a survivor. At its heart, it’s the story of a woman who risked everything to find the daughter, Niyat, she had left behind in war. It was only when Yordy found safety in Australia that she could begin the dangerous quest to find her. Most of us will never know what we would do to simply survive. Yordy does; she lives with those choices every day.

Her memories of being an unloved and abandoned girl come to the surface in fragments. Her father’s family were middle-class, with land and houses, but they didn’t take her in after he abandoned her.

“I didn’t feel sorry for myself,” she recalls. “Sometimes, I would stay in a stranger’s house. I would look at them to see if they were okay and the next day I would move out. I never stayed in one place; I was always moving.”

She would go to her mother’s house, where her cousins were staying, “but none of them would ever house me or take me. I don’t know why”. She would ask strangers for food, or grab food from other children.

“Whatever I needed, I would just find.” She often slept outside. “I grew up in the street.”

When Yordy was five, the army came carrying guns.

Child soldiers in Africa. PHOTO: Getty.

“They just put me in a truck.” For the next decade, she was a soldier in the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front, which was fighting for independence from Ethiopia. And rape, she says, was endemic.

“In that place, I let them do whatever they needed to do to my body, which is basically that they raped me. The sad thing was that they didn’t get any pleasure, they were so angry. It was outside of me – that helped me to survive,” she says. There were pregnancies and abortions. “I didn’t know what was happening with my body. I didn’t know what pregnancy was. There was no explanation.”

She often ran away. “Usually I stayed for three days in the bush, then when I was really, really hungry, I would come back, or when I was scared from the hyenas in the bush. And then they would cage me in a tiny cage, to punish me for running.”

By her early teens, Yordy was striking-looking. One of the leaders took her as his partner. “I felt safe with him, I wasn’t hunted by other men,” she says. “He was very protective. I travelled wherever he travelled because he didn’t trust his own men.”

Child soldiers in Africa. PHOTO: Getty.

Then, at 14, she was pregnant. He wanted an abortion but at seven months, the doctor refused.

After the baby, a girl named Niyat, was born, Yordy was damaged goods, too much responsibility. He lost interest.

“He wanted us both to disappear.”

He did the closest thing: he sent her back into the fighting.

Yordy was forced into a decision no mother should ever have to make. She was going to the front-line, from which people didn’t come back. She thought Niyat would have a better chance if she left her with her father. He had a family, she didn’t. “The chances with him were 50 per cent, but with me it would be zero, I was going to death. I couldn’t choose for her to die with me.”

The front-line was, she says, intense, a place beyond fear. “Constant bombs from the planes, from the enemies,” is how she puts it.

“If you are in the middle of war, you don’t get scared. I have never had any fear at all. Part of you dies, anyway.

After a while, it becomes a game really. When the bomb comes, you just need to know how to hide and to try your best not to get bombed.”

During one skirmish, Yordy took her chance to run. “There were a lot of bombs happening. Everybody went different ways, our leaders were gone – that was my opportunity.”

She stayed in the bush for a week, then went to the Ethiopian army and handed herself over, saying she wanted to go to Sudan.

Instead, as a suspected spy, she was kept prisoner for three years. At this point, Yordy hunches over, tears rolling as she struggles with the memory of her treatment. Here, she discovered the strength of her mind, that she could go somewhere else in her head.

“In the extreme abuse and jail, I never gave my mind at all,” she says.

“I let them abuse my body, but they never controlled my mind. In my mind, I can escape them. I can see something they can’t see.”

PHOTO: Getty.

Finally, she got away, trekking through the desert for six weeks to Sudan, holding to the hope that life had to be better, somewhere. She didn’t know about Western countries, but when she registered as a refugee, she had the foresight to register her daughter, too.

The UN organised for her to go to New Zealand. By then, she was pregnant to the man who was her interpreter. When they arrived in Auckland in August 1994, it was raining. “New Zealand was a complete shock,” she says. “I was never the same woman ever again. That numbness was immediately gone. I was a totally different person. I just loved it.”

She was 19, spoke no English, didn’t know about money, or even how to live in a Western country. It was a long time before she understood she was safe.

Yet she was isolated. She knew she had to learn English. “I was desperate. I couldn’t understand anything.”

A Jehovah’s Witness who knocked on Yordy’s door got more than she had bargained for. “She had a book with her. And she asked me very carefully in English, saying, ‘Do you want to learn the Bible?’ I said yes. I said, ‘You read English and I will read my language, and then we will swap.’ Three years later, I could read books.”

It was a real sense of freedom. Now, she devours books and documentaries. “That is how I educate myself.”

Yet she was still running. Wellington, Christchurch, and then – in 2000 – Sydney. Although Yordy now had three sons, the need to find her daughter became primal. “All I could think was that if I could find my daughter, I would be complete,” she says. It was dangerous for her to return to Eritrea – she was an army deserter. They might arrest her, even execute her. Yet when she landed back in Asmara in 2006, there was that familiar smell of Africa.

“I knew who I was in this place.”

Yordy had been reported as dead, so it was as if a ghost had arrived. Niyat, then 16, was with her father’s family.

He had died, but there was a photo of him on the wall. “He was a handsome guy.” To his family, he was a war hero.

There was no ecstatic reunion. Niyat was angry, suspicious. She had thought her mother was dead, now she learnt she had been abandoned.

There was no birth certificate, so Yordy did DNA tests in Kenya. A year later, Niyat arrived in Australia, two weeks before she would have been drafted into the army. It has not been an easy passage. They were strangers from vastly different cultures. And Yordy’s sons have had to adjust to the shock of having an older sister. Yet, says Yordy, “We have a very honest relationship. She is fabulous girl, she is kind, she is a nurse and she has just got into postgraduate midwife studies.”

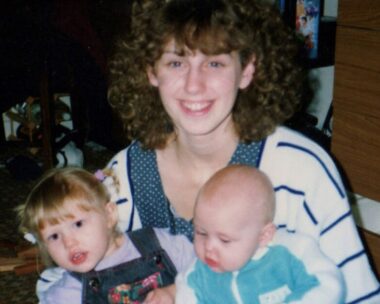

Yordanos Haile-Michael and her daughter, Niyat (right) after their reunion.

Yordy has been back to Eritrea four times now, but she has never found the acceptance she was looking for from her family. “I wanted them to hug me and love me. None of that was there. They still can’t see me. I learned that they can’t see any different. I had to let it go. There is no apology.”

When she went back to get Niyat, she ran into one of her rapists at the airport. “There was an awkward silence and I asked why he did what he did,” she says. “He said everybody was doing it. It was a victory [for me] because I was taking my daughter out of Eritrea. I felt sorry for him.”

Today, Yordy works in aged care and sees a psychiatrist every week. She is still learning how to live. “I learn every day how much I don’t know: how to be a mum, how to cook for my children, how to relate to people. I take something [useful] from everybody, every day. I focus on my children. I take it quite seriously never to repeat what happened to me, so that pain and dysfunction doesn’t pass onto them.”

She feels for other children caught up in military conflicts at home and in other countries. “No child deserves to be a child soldier. Every child deserves to be protected. A lot of children died in the war. I can still see them, they live with me every day. I try to make sure I live a better life for them.”

Yordy has learned to fight violence and brutality with compassion and love, knowing that anger consumes you and eats you from the inside.

“We all have a story,” she says. “It is how we care about each other and have understanding that matters. I never felt anger or wanted revenge. I don’t think conditions apply to compassion.”

Besides, there is a kind of revenge in surviving.

“I found me. They didn’t take the best of me and I am okay with that. We have such responsibility as mums and dads to raise boys with respect for women. It starts at home.”

Yordy and other cast members in the film.

In 2010, Australian theatre director Ros Horin was looking for women who were willing to share their stories of extreme hardship and Yordy was one of the first she met. Ros gathered enough material for a play and a documentary film, The Baulkham Hills African Ladies Troupe. Set around four African women telling their stories, the play was a hit in Sydney in 2013, then London in 2015.

Ros hoped the process would be healing, but for Yordy it was a bumpy ride, the opening up of old wounds. She says it felt like she was being set on fire.

Yet now, with her children safely by her side, Yordy is learning to move beyond her painful past and come out the other side.

The Baulkham Hills African Ladies Troupe film opened nationally, October 6. Visit africanladiestroupe.com.

A version of this story first appeared in the October 2016 issue of The Australian Woman’s Weekly.