The arrival of 2016 marks ¬ five years since she went to jail for the 1996 murder of her newborn daughter, Tegan . It means it will be another eight years before she is eligible for parole. And most signi¬ficantly of all, if Tegan is still alive – as Keli fervently maintains is the case – the little girl who never was would be turning 20 later this year.

Each is a milestone that Keli will mark while behind bars. Friends and family who have spoken to The Weekly for this special two-part report say she has undergone a remarkable transformation in prison.

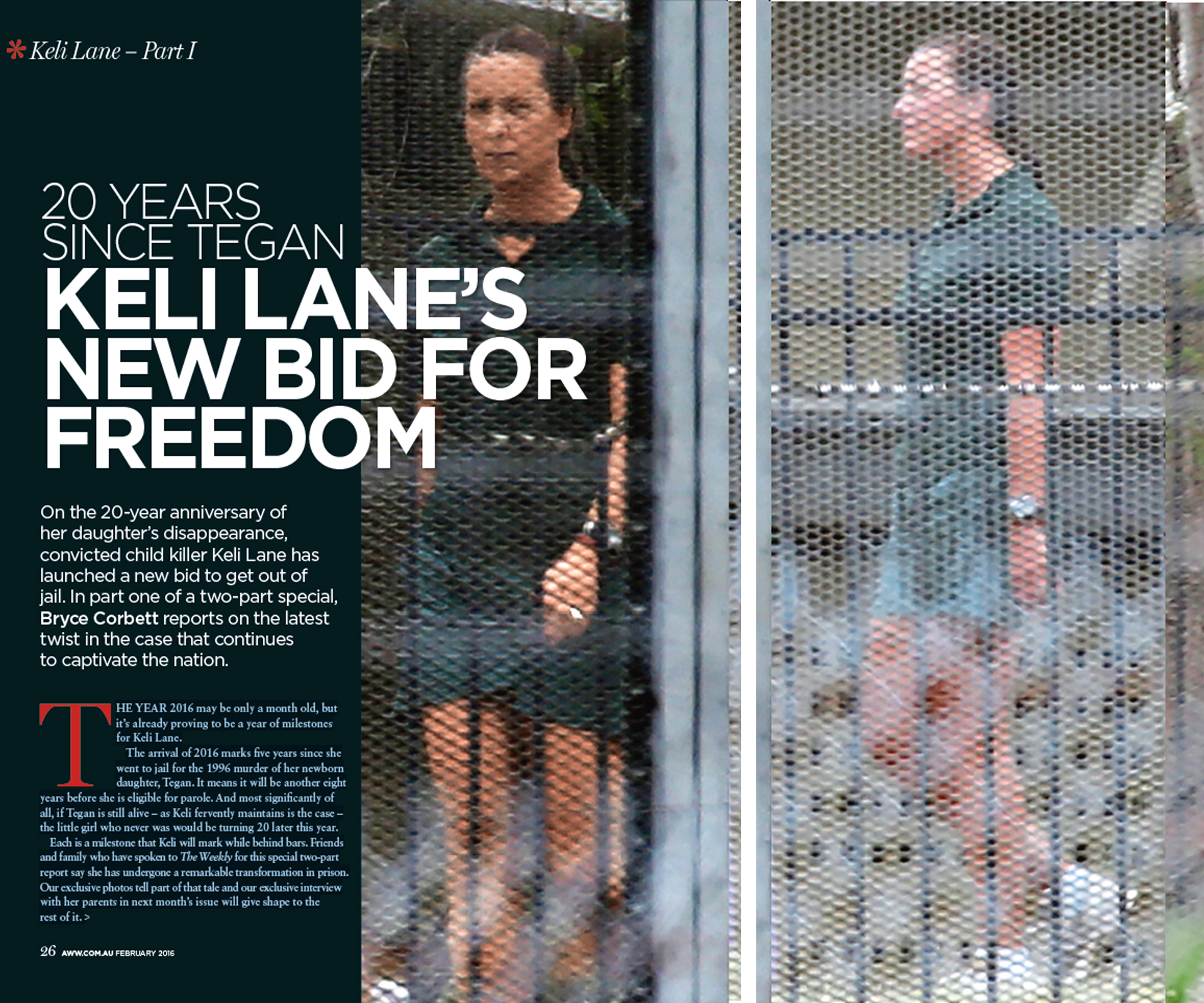

Our exclusive photos tell part of that tale and our exclusive interview with her parents in next month’s issue will give shape to the rest of it.

Meanwhile, the year 2016 also marks the start of a new – and last ditch – attempt by the now 40-year-old convicted child killer to be released from prison and clear her name.

Despite two unsuccessful legal appeals against her sentence – the latter of which went to the High Court – the former water polo champion has had a recent victory of sorts.

Her case has been taken on by a Melbourne-based group of lawyers and academics that is determined to prove she was wrongfully convicted.

Recently formed The Bridge of Hope Innocence Initiative, operating out of RMIT University, has confirmed to The Weekly that it has taken on Keli Lane’s case for examination.

The aim of The Innocence Initiative is to analyse the trials of select Australian prisoners to determine if there has been a miscarriage of justice. Its patron is former Victorian Governor David de Kretser and its board members include his son, Hugh de Kretser, Executive Director of the Human Rights Law Centre. In the US and UK, similar organisations have worked successfully to free from prison hundreds of people who have been wrongfully jailed.

It’s the latest twist in a tale which continues to baffle legal experts and observers alike. Certainly, in the recent history of the Australian penal system, no other case has been more confounding first , a refresher. In 2005,Keli Lane became a regular and increasingly fascinating fixture on the evening news bulletins around the country as a coronial inquest into the disappearance of her baby daughter, Tegan, unfurled. The Australian public watched on with mouths agape as the court heard how across a period of four years from 1995 – and while she was otherwise going about her normal day-to-day life – Keli had somehow secretly carried to term and given birth to three children.

The first and third of her secret children – a little girl and a little boy – were adopted out through official channels. The second-born, Tegan – who was delivered by lone 21-year-old mother Keli at Sydney’s Auburn Hospital on September 12, 1996 – disappeared two days after she was born.

For a full three years, no one noticed Tegan was missing (for how do you miss a child whom hardly anyone knew existed?) until, during the process to adopt out her third secret child, a social worker stumbled across Tegan’s hospital records.

After an inconclusive police investigation that sputtered along for six years – including unsuccessful attempts to find even a trace of Tegan – a coronial inquest was held, which gave rise four years later to a murder trial. During the trial, Senior Crown Prosecutor Mark Tedeschi QC posited the theory that Keli killed two-day-old Tegan and disposed of her body at the Homebush Olympics building site because she wanted to attend a wedding later that day – and because she harboured a burning ambition to play water polo for

Australia at the 2000 Games. Even if, back in 1996, women’s water polo was not an Olympic sport. Keli maintained she had given the child to its biological father, a man she had only known briefly and couldn’t be certain if he was called Andrew Morris or Andrew Norris.

At the end of 2010, a 12-person jury found Keli guilty and, four months later, she was sentenced to 18 years in prison.

Since then, a number of voices have been raised about whether justice was served in Keli’s case. Much of the disquiet has centred on the approach to the trial taken by Mark Tedeschi, whose successful convictions in the high-profile murder case of Gordon Wood and the Hilton bombing case involving Tim Anderson were both subsequently overturned on appeal, resulting in both men being release from prison.

In her five years in jail and, indeed, throughout the 15 years since police began asking questions, Keli has never wavered from her story that she gave Tegan to her biological father at the hospital as she was leaving: a man whose name she doesn’t remember. And for a decade now, the only thing more constant than Keli’s adherence to that story has been the Australian public’s unwillingness to believe it.

Now though, with The Innocence Initiative taking on her case, focus is set to turn to whether someone should go to jail for murder when there is no proof of a death having actually occurred, nor any credible motive.

Even the judge at Keli’s trial, the now retired Justice Anthony Whealy , has expressed his misgivings on this point. In his summing up and before he despatched the jury, he went as far as to suggest that a guilty verdict would be wrong.

“There is no direct evidence that Tegan Lane is dead,” he told the jurors. “There is no direct evidence, even if she be deceased, as to the cause of that death, or when it happened. This is an unusual trial in this sense because the fundamental facts you would expect to ¬find in a murder trial are completely absent.

“It is important that you do not speculate,” Justice Whealy continued.

“You could not say to yourselves, ‘Oh, we don’t know what happened to Tegan, we don’t know where she is, and I suppose for that reason we should conclude that she is dead.”

Two years after the trial, Justice Whealy admitted he remained “emotionally affected” by the case, telling The Sydney Morning Herald: “I wasn’t, for myself, convinced that the Crown had proved its case. It wasn’t my call, it was the jury’s call, so my task was to try and make sure that the jury gave the woman a fair trial.”

Two years after the trial, Justice Whealy admitted he remained “emotionally affected” by the case.

According to Dr Xanthe Mallett , a forensic anthropologist at the University of New England and author of Mothers Who Murder – a book that examines the cases of renowned convicted child killers including Kathleen Folbigg and Rachel P¬ tzner – Keli’s case is worthy of re-examination.

“The lack of a body, the fact she had never been violent before and she adopted out two other babies, plus the fact she is clearly a smart woman makes me ask: why would she kill a baby?” says Dr Mallett.

“Clearly, Keli was never in line to win a Mother of the Year award and she disgraced herself by lying so often and so fragrantly, but it’s still a big leap to say she killed her baby.”

Dr Mallett believes Keli was a victim of “trial by media”.

“The same thing happened to Lindy Chamberlain ,” she says. “People thought she wasn’t emotional enough and didn’t respond in the way a mother should, so clearly she must have been guilty.

“In Keli’s case, she was also judged on the basis of having given up children for adoption and undergone pregnancies in secret.”

Senior Lecturer at the University of Southern Queensland, Dr Andrew Hemming, has also been examining Keli’s case. A specialist in miscarriages of justice (his paper on the legal inconsistencies that preceded the wrongful conviction of Gordon Wood for the murder of Sydney model Caroline Byrne was published in the University of Notre Dame Law Review in 2013), Dr Hemming has told The Weekly he believes there are sufficient holes in the legal case against Keli to warrant investigation.

Even if he thinks her chances of exoneration are slim.

“Keli contacted me via letter,” he reveals.

“Because, in Mark Tedeschi, she had the same prosecutor as Gordon Wood and she had read my paper. The difference [from Gordon Wood], however, is that Keli’s case has already been considered and rejected by both the Court of Criminal Appeal and the High Court of Australia.

And that means she’s exhausted all avenues of legal appeal.”

Dr Hemming said the only hope Keli now has of avoiding serving the remaining years of her sentence is if she applied to the NSW Governor for a pardon, for which she or her legal team would need to produce “fresh and compelling evidence” not already heard in her trial. “And in Keli’s case,” says Dr Hemming. “That means either Andrew Norris coming forward or Tegan suddenly appearing. Or if she changes her story.”

And with the passing of every year, the likelihood of either of these events occurring seems ever more remote.

The days pass slowly when you are in prison. You develop whatever routine you can to stave off the boredom as the human desire to be productive in any given 24-hour period is stifled by your circumstances.

Keli is currently being held in a minimumsecurity facility outside of Sydney. Along with the other convicted child killers with whom she shares prison space – including Kristi Abrahams, who killed her daughter Kiesha and stashed her in a suitcase before dumping her in bushland – Keli spends her time in protective custody, separated from the jail’s general population.

Life as a high-profile inmate is not easy. It makes her a target for prison officers as well as fellow prisoners. Even so, Keli’s parents say she has forged tight bonds with many of her fellow inmates, providing “mentorship” to a handful of fellow prisoners and “helping some girls to get off drugs and turn their lives around”.

She spends her days exercising, both inside and outside her cell, and writing to legal experts all over the country whom she hopes can help her. She has become a vegetarian and has lost 10 kilos in the process. Her famous peroxide blonde locks have returned to their natural brown. Most notably, she has spent the past year working on a 193-page document: a forensic analysis of the case that was mounted against her and a detailed listing of what she believes are the major flaws in it.

Friends who have seen it describe it as comprehensive and packed with an impressive grasp of criminal law and legal precedent.

She receives visitors almost every weekend – including her partner Patrick and her parents Sandra and Robert.

Keli’s daughter visits most weeks in the company of her grandmother, Sandra.

Now 14 and in the full-time care of her father and his new wife, the remarkably well-adjusted teen also spends a lot of time in the company of Keli’s parents.

The financial cost of defending herself throughout almost a decade of legal proceedings has exceeded half a million dollars. And that’s nothing, her parents say, compared to the emotional toll it has taken on her family.

In a secretly recorded phone conversation with a friend in 2004, when the pressure was being applied by police investigators, Keli broke down in tears.

“I’m frightened. I’m so scared I am going to lose [my daughter],” she says.

“I haven’t slept in four days. I haven’t eaten. When my parents find out – it’s going to blow wide open and they are going to be so embarrassed and ashamed. I feel like I used to spend all this time worrying about being a sports star and achieving all these wonderful things, but the only thing I am really good at is being a mum.”

There’s no question that Keli has broken the law. She lied repeatedly to police and committed perjury. During the trial, the media portrayed her as cold and remote – not the least bit remorseful.

Yet then if, as Keli claims, she hasn’t done anything wrong, what does she have to feel remorseful about? And yet, even her staunchest supporters are hard-pressed to say they entirely believe the Andrew Norris story.

In five years of reporting on this case, few of Keli’s friends willing to talk have been able to say they believe her unreservedly.

They believe Tegan is alive – or at least, if she is dead, that Keli did not murder her. Yet the persistent sense is that there is some other truth that has not been told.

And that whatever that truth is – she sold Tegan in a private surrogacy arrangement, she left her somewhere in a panic, or gave her away to persons unknown – it’s sufficiently awful in Keli’s eyes for her to stick to her Andrew Norris story.

As Dr Xanthe Mallett says, “It’s a big enough secret that she is prepared to serve a prison sentence rather than reveal it.”

And then there are those who wonder at Keli’s mental state.

A psychiatrist assessed Keli from a distance during her trial, relying solely on video of her initial police-recorded video interviews, but no other formal psychological examination took place before she went to prison. Could she suffer from some sort of mental disorder making her believe wholeheartedly in an alternative reality?

Or could it be she is simply telling the truth? Unlikely as it may seem, Tegan’s biological father may have taken his daughter. And for reasons we may never know, he may have changed her identity, taken her overseas or raised her to believe she is someone else completely. It’s not impossible. Highly improbable perhaps, but not impossible.

As Justice Whealy conceded to The Weekly last year when contacted for his thoughts, “It’s a case that continues to confound me.”

The question The Innocence Initiative will seek to answer is this: did Keli Lane go to jail because there was incontrovertible evidence she murdered her baby, or is she in there because as a society we find her secret pregnancies, clandestine adoptions and multiple lies morally dubious?

The bigger question, of course, is what really happened to Tegan Lane? And it’s still entirely possible there’s only one person alive who knows the answer to that.

TIMELINE

MARCH 1995

Baby “Tahlia” born in secret and adopted out.

SEPTEMBER 1996

Baby Tegan born in secret.

MAY 1999

Baby “Aaron” born in secret and adopted out.

NOVEMBER 1999

A DOCS worker becomes suspicious and reports “disappearance” of Tegan to police.

FEBRUARY 2001

Police interview Keli. At this stage, the matter is treated as an “occurrence”.

APRIL 2001

A baby girl is born. She remains in Keli and her new husband’s custody.

OCTOBER 2002

Detective Richard Gaut takes over case. He interviews Keli the following May.

JUNE 2005

A coronial inquest begins into the disappearance of Tegan Lane.

NOVEMBER 2009

Keli summonsed to stand trial for murder via “ex-o¬ffcio indictment”.

JULY 2010

Murder trial begins.

DECEMBER 2010

Keli found guilty of murdering Tegan, sentenced to 18 years in prison, with a 13 year, five month non-parole period.

DECEMBER 2013

NSW Court of Criminal Appeal rejects Keli’s appeal.

AUGUST 2014

The High Court of Australia denies Keli’s appeal.

JANUARY 2016

Keli’s case is taken up by The Innocence Initiative at RMIT.

A version if this story originally appeared in the February 2016 issue of The Australian Women’s Weekly. You can pick up a copy of The Weekly’s March issue ON SALE NOW to read part-two – an interview with Keli Lane’s parents.

WATCH: What’s in The Weekly this month?