If you’ve fallen in love and can’t for the life of you understand why then we have some news for you. Turns out your brain made you do it. And your brain made you choose the person you fell in love with you too. It’s not particularly romantic. But it is true, says Dr Helen Fisher, a biological anthropologist at Rutgers University.

Dr Fisher has dedicated her life’s work to researching and explaining the way love has evolved over centuries. Her scientific investigations explore love’s mysteries and explain human behaviours through the biological and chemical responses in the brain.

So what does science have to say about the different phases of love, why we are attracted to one person and not another, and how we can keep love alive in our long-term relationships?

To begin with, Helen says there are three distinct phases in desire for a partner: sex drive, romantic love and feelings of attachment. Each phase is directed by a different chemical system in the brain, and the phases do not necessarily happen in sequence, she says.

“You can fall madly in love with someone you’ve never slept with. You can feel deep attachment for someone you knew in college or met in business and then fall romantically in love with them. Or you can be not at all in love and have no attachment and just hop into bed with them because it’s late and you’ve had too much to drink,” she says.

The sex drive is driven by testosterone in the brain. It is this drive, Helen says, that “gets you out there” to look for a mate. Without it we might become complacent and prefer to stay home on the couch, she says.

The phase of attachment, usually associated with long-term relationships, is driven by serotonin, high oxytocin and vasopressin, which bring feelings of calm and happiness, Helen says.

The overpowering phase of romantic love is driven by dopamine in the brain, Helen says.

Dopamine is linked to the brain’s reward systems that are associated with craving, motivation, high energy and focussed attention: all involuntary states that are difficult to control, Helen says.

“The drive to romantic love is not an emotion. It comes from primitive regions in the brain,” she says.

“When you are in romantic love, the person takes on a special meaning. Everything about them becomes special: their car, the music they like,” Helen says.

So what is that drives you to ascribe special meaning to one person and not another?

This is the question that Helen has set out to answer.

The existing evidence had showed that people are attracted to each other based on issues such as timing and proximity, sharing similar cultural and socio-economic backgrounds, education and social values, a similar degree of good looks, and similar reproductive, economic and social goals, Helen says.

While she accepted these findings, Helen felt they didn’t explain the full story. If you entered a room of people – all of whom might be compatible based on the above list – why are you then drawn to one particular person among the group?

“People say, ‘We had chemistry, we didn’t have chemistry’. We wanted to know: what does this mean?” says Helen.

After surveying more than 13 million Americans via two popular dating sites, Helen identified four distinctive biologically-based styles of thinking and feeling that could be used to predict the attraction commonly referred to as ‘chemistry’.

People who are dominated by the chemical type dopamine, which Helen has labelled ‘Explorers’, are known for being sensation-seeking, enthusiastic, optimistic, impulsive, independent, restless and unreflective.

“This type is drawn to people like themselves,” Helen says.

The second type has higher levels of serotonin, or the ‘Builders’ characterised as being conventional, conforming, controlled, orderly, persistent and as having lots of close friends, respecting authority and being frugal and cautious.

People in this group are also attracted to others of the same type. The next two chemical types, however, are attracted to those in the opposite category.

The high testosterone type, labelled the ‘Director’ – known for being analytical, logical, inventive, competitive, decisive, bold, direct and demanding – are attracted to their opposite, the estrogen and oxytocin type, called the ‘Negotiator’. People in this type are imaginative, intuitive, trusting, emotionally expressive, diplomatic, compassionate and agreeable, and they are attracted to the high testosterone ‘Director’.

These chemical types help establish who is naturally drawn to whom, Helen says. “And they show we inherited a brain circuitry for love patterns.”

Love has a lot to do with chemicals y’know.

THE FOUR CHEMICAL TYPES

The Explorer: high in dopamine. Curious, sensation-seekers; attracted to their own type.

The Builder: high in serotonin. Sensible and loyal; attracted to their own type.

The Director: high in testosterone. Analytical and decisive; attracted to their opposite (the Negotiator).

The Negotiator: high in estrogen and oxytocin. Intuitive and compassionate; attracted to their opposite (the Director).

Understanding who you are drawn to and why is an important part of Helen’s research on the brain in love. But another question that dominates our romantic relationships, and Helen’s research, is: how do we stay in love, and what is it that makes some couples so much happier together than others?

The dopamine-driven ecstatic highs and euphoria of the romantic love phase also come with uncomfortable feelings of anxiety, frustration and obsessive thinking, and it is a state that is not considered to be sustainable, Helen says.

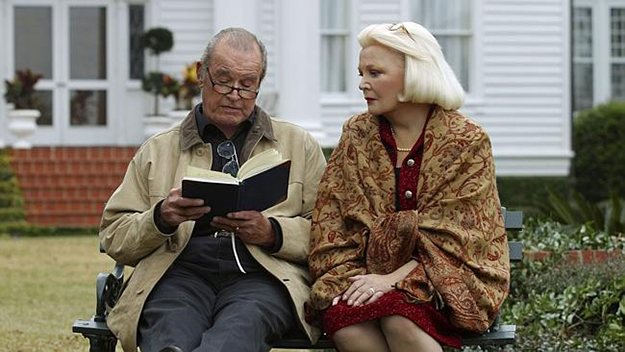

But Helen and her researchers kept hearing about couples who said they were ‘madly in love’ even after decades of being together.

“We wanted to know: can romantic love last? We thought ‘No’, but we’d heard of people in their 50s and 60s who were still ‘in love’. So we put them in the brain scanner,” Helen says.

The brain scans showed that couples who reported being in love had more activity in the region of the brain that is associated with mirror neurons.

“This is the brain region linked with empathy and with happiness,” she says.

Responses in this part of the brain help people maintain positive illusions and suppress negative judgments, traits that help sustain a happy relationship, she says.

Helen’s research also set out ways couples can interact with each other to keep on activating the chemicals in their brain that make them feel in love, including more touching and kissing and giving each other at least five affectionate comments each day [see breakout].

This era of our history is characterised by people marrying for love and spending significant time and focus on making sure their primary relationship is a happy one, Helen says.

“If there was ever a time in human evolution to make happy marriages – that time is now,” Helen says.

“We are marrying to please ourselves, we are working harder on our relationships, and we are starting to believe that a good relationship with another human being is the most important thing on this planet.

But how to make the love last?

To sustain happy partnerships:

– Keep up your positive illusions of each other by emphasising the positive: this drives dopamine, which sustains feelings of romantic love;

– Touch each other by walking arm in arm, or placing foot on foot under the dinner table, or fall asleep in each other’s arms: this drives oxytocin, which raises feelings of attachment;

– Kiss regularly: this also raises oxytocin;

– Have sex regularly: this drives testosterone (which further increases the sex drive), drives dopamine and feelings of romantic love, while orgasm floods the body with oxytocin bringing deep feelings of attachment.

– Make affectionate comments to each other five times daily: this has been shown scientifically to lower your partner’s cortisol, or stress hormone. Giving affectionate comments is also good for your own cortisol levels.

Note: Helen Fisher is the author of Why Him? Why Her? (Henry Holt, $19.95).

A version of this article originally appeared in the February 2014 issue of The Australian Women’s Weekly.